When the 12th writes stories for ‘The People’s Game,’ we focus on portraits of the people who make this community incredible. Think immigrant stories, family connections, amateur and grassroots efforts to uplift each other.

The top flight of Mexican football may soon welcome a legendary Mexico City club back into the fold. The Mexican Football Federation has approved Atlante, otherwise known as Los Potros de Hierro–“the Iron Colts”– to return to Liga MX after a decade in the country’s second tier.

For the azulgrana–referring to the blue and garnet stripes of Atlante’s kit that mirror Barcelona’s–this represents a return to greatness. The club’s history includes forward Juan Carreño scoring Mexico's first World Cup goal, against France during the 1930 games in Uruguay.

They were an original member of Mexico’s top league and played in the largest stadiums in Mexico’s Capitol–first the Estadio de la Ciudad de los Deportes and then Estadio Azteca, now known as Estadio Banorte.

Across the Gulf of Mexico, in the Atlanta suburb of South Cobb, another club is diligently working to climb the tiers of the U.S. football pyramid, such as it is.

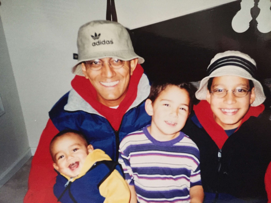

United by more than a love for the game, Christopher and Benjamin Uranga formed an amateur club in 2016 with the goal of living out the values their father, Luis, had instilled in them. Namely, that a football club was for the community, and should be judged as much by its culture as by its play on the field. In thinking about the name for their club, the brothers were inspired by the team their father Luis and his father, also Luis, had played for back in Mexico City: Atlante.

They named it Potros FC.

A Family Affair

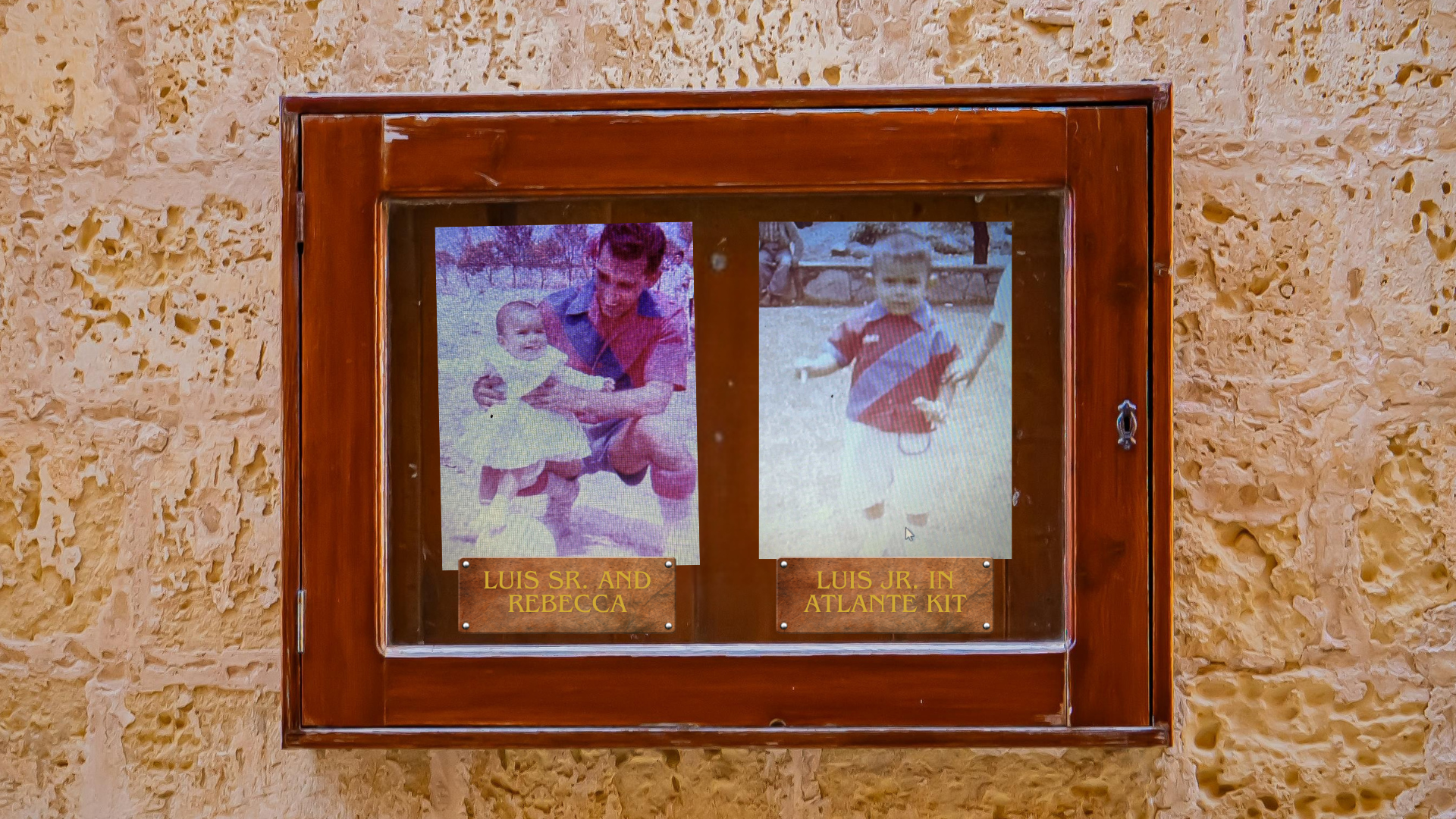

“We’ve always supported Atlante,” Christopher tells Timothy and I over a lunch break phone call. “My grandpa played for them. My dad played for their reserve team, and we’ve supported them my whole life.”

His father, Luis Uranga, remembers a childhood steeped in the sport. Speaking with Vanessa Angel in 2021 for a post on her blog, Soccer Talk, he recalled how his own father would take him to practice sessions for Atlante.

“My father tells me that I was sort of their honorary mascot because I was there so often,” Luis told Angel. “I was practically part of the team, they even got me a uniform”.The elder Uranga earned an invitation to the Mexican National Team for the 1952 Summer Olympics, but his dreams were crushed by a late cut from the roster.

For his part, Luis was invited to play with the youth teams of Cruz Azul and then made it onto Atlante’s reserve team – where it all started. After about six months , Luis faced a difficult choice: continue his playing career or stay at home and finish college. He needed another job to pay for school, so with the strong urging of his own father, Luis ended his career.

After graduating, he came to the United States on vacation and met Meryl, his wife. Together, they had four children: Nicholas, Rebecca, Christopher, and Benjamin.

Little did he know, he would eventually coach for Los Potros – just not the one he had grown up with.

Going as Far as They Can

Christopher realized as a young man in Cobb that if his family wanted to keep playing soccer, they were going to have to make it happen themselves.

“Growing up in Powder Springs, American football and basketball were always the really popular sports. There wasn’t much opportunity to play soccer where we lived, so as we got older, we used to offer training in the summers and stay involved in the community. After high school, we got a couple of friends together and started playing in the local amateur league.”

Christopher and Benjamin played on their makeshift team, with Luis as head coach and their sister Rebecca training and playing with them as her school schedule allowed. They played most of their games out of Franklin Gateway Sports Complex in Marietta, but their eyes were firmly on the horizon.“We learned in our first season in the Atlanta District Amateur Soccer League about a competition called the Perrin Cup. The winner of the Perrin Cup would automatically qualify for the U.S. Open Cup. If we win the Open Cup, we can qualify for the CONCACAF Champions League. And if we win the Champions League, we can qualify for the FIFA Club World Cup and be World Champions.”“So that was our goal, to win the Club World Cup,” he says with only a hint of laughter.

It’s been a grinding path forward. The team joined the United Premier Soccer League in the fall of 2020––the professional development league that includes Atlanta United’s under-19 academy team. After a last place finish their first season, they’ve steadily improved by focusing on the team’s culture, learned from Luis, who coached the team their first several years. One season the team has made the league’s playoffs; the next season, no.

The team’s culture includes what Christopher calls being “very strict” with players. If you miss training, you don’t get on the game roster. Players have to show up 90 minutes before gametime and be respectful to referees during the game. The squad ranges in age from 18 to 38, natives of South and Central America, Africa, the Caribbean and Europe.

The team’s culture also borrows inspiration from Atlante FC’s nickname: “el equipo del pueblo,” or “the people’s team.”

“It doesn’t matter what your background or social status is; we don’t have sponsors or investors, and anyone can be a part of [Potros FC],” Christopher said. “We don’t make a profit. We’re not going to ask players for thousands of dollars.” One season, the team wound up $3,000 short. Nonetheless, the team charges players only $500 a season to cover the costs of uniforms, referees, coaches, and field rentals.

They also livestream all of their matches to YouTube in order to support players' exposure and ensure their family members and fans can tune in even if they live further away.

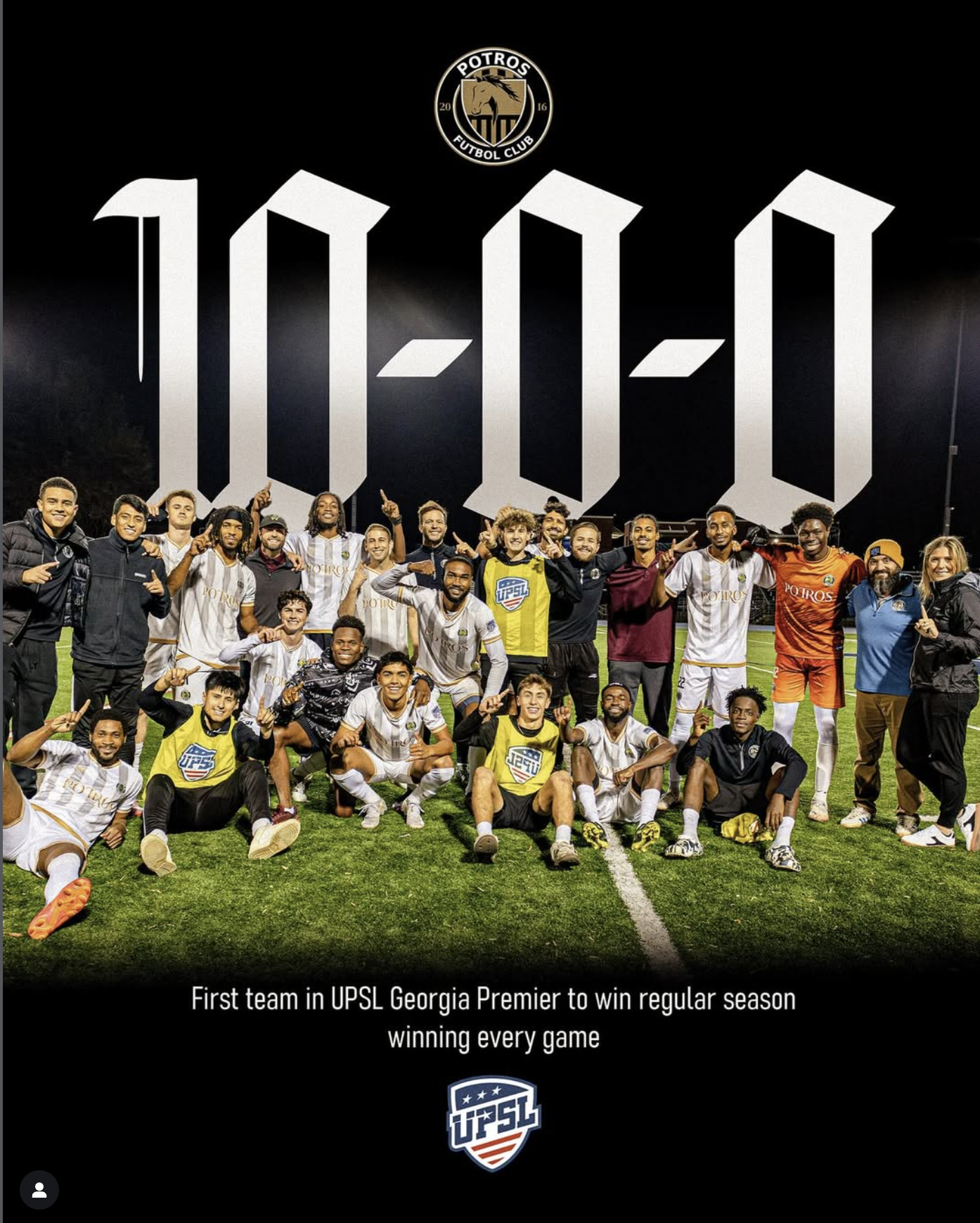

In 2025, Potros FC went 10-0 - the first time that had happened in the UPSL's history. At the same time, the club had made it to the final round of Open Cup qualifying after a Round 1 bye, and victories over North Georgia United and Atletico Buford in the following two matches. That meant a chance to play Kalonji Soccer Academy Pro-Profile (KSA), who also finished first in the UPSL’s other Georgia division. The winner would then qualify for the Spring 2026 U.S. Open–the first major tournament on Christopher’s bucket list.

A Chance at the Open Cup

Officially called the Lamar Hunt U.S. Open Cup, the tournament dates to 1913. Pitting amateur clubs against MLS and semi-professional clubs in a knockout format, it is the only glimmer of meritocracy on a U.S. football landscape almost completely lacking promotion and relegation, the system used in the rest of the world.

In short, if you keep winning, you keep advancing. If you lose, you go home. This is not true in MLS, for example, where you can lose every game in a season– and still stick around!

Since MLS launched in 1996, the tournament has acquired the David and Goliath significance of other open tournaments worldwide for dozens of U.S. teams like KSA and Potros FC.

Nonetheless, MLS teams have held onto the trophy every year but one. Not only that, the league has shrunk the target on its back in recent years by reducing the number of teams that enter the competition.

Next year, 16 of the tournament’s 80 teams will come from MLS.

The big chance for Potros FC to be among those 80 teams arrived on Nov. 23, a night where temperatures would dip into the 40’s.

This didn’t keep several hundred fans away from the high school stadium built for the other football. It was one of the top ten crowds ever for Potros FC, Christopher would later tell us.

Dozens more followed a livestream broadcast of the game by the Atlantic Soccer Media Group, an outfit formed in 2021 based on the premise that “competition in lower league soccer in the United States is being underserved by [a] lack of broadcasting opportunities,” according to its website.

About 15 minutes into the game, a steady beat could be heard coming from outside the stadium. A handful of Congolese supporters of two fellow countrymen playing on KSA entered the stadium; one was towing a speaker on wheels behind him. They soon set up a choreography to go with a song from their homeland blasting from the speaker. One explained to me that the song’s chorus was about whipping someone; the dance mimicked that action.

Looking back at the recording of the livestream, it was also around this time that the announcer asked viewers: “Can one of these semi-pro teams make a run in the US Open Cup? Maybe break the hearts of some of these… MLS teams?”

But it was not to be Potros FC. At least not this year.

The game was pretty chippy, the ball was in the air quite a bit. It was no surprise that the difference between the two teams wound up being a handball penalty in the 55th minute. KSA defender Grant Carr put it on the ground and into the net.

A few days later, Christopher was still smarting from the call, but undeterred. “It was a great experience, for our first attempt” at entering the Open Cup, he said. “We played with dignity.”

If you enjoyed this piece, please consider donating whatever you can to help keep The 12th running. We can only do more of this with your support.